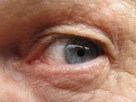

In addition, vitamin A is an essential part of vision. The first signs of vitamin A deficiency, which can also be an issue for the elderly in developed countries, include night blindness, and persistent deficiency can result in total vision loss. Supplying an adequate amount of vitamin A or its precursor beta-carotene is vital for good vision (30).

In the eye, vitamin C is highly concentrated in the lens, where it works as an antioxidant. Numerous scientific studies have linked increased intakes of vitamin C alone (31) or in combination with other antioxidants such as vitamin E, beta-carotene and zinc (32) with long-term protective effects against the development of cataract and AMD in an older population.

Also the vitamins B9 (folate / folic acid), B6 and B12 have been shown to reduce the risk of AMD (33), probably by reducing the blood concentration of homocysteine, which is thought to be a risk factor for diseases of blood vessels, like AMD.

Furthermore, the omega-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), an important component of retinal pigment cells, and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) are vital for an optimal function of the eye. A high intake of DHA and EPA has been associated with a 40% reduction in the risk of AMD (34).

While the march of the years cannot be stopped, some lifestyle factors can increase the chance for healthy aging: not smoking, regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, a moderate alcohol intake plus eating a balanced, micronutrient-rich diet including plenty of fruit and vegetables. Elderly people are at increased risk for micronutrient deficiencies, and should ensure

While the march of the years cannot be stopped, some lifestyle factors can increase the chance for healthy aging: not smoking, regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, a moderate alcohol intake plus eating a balanced, micronutrient-rich diet including plenty of fruit and vegetables. Elderly people are at increased risk for micronutrient deficiencies, and should ensure  The aging process

The aging process Cardiovascular system

Cardiovascular system Mental performance

Mental performance Mobility

Mobility Vision

Vision Hearing ability

Hearing ability